A journey in…

Authentic and pure flavours

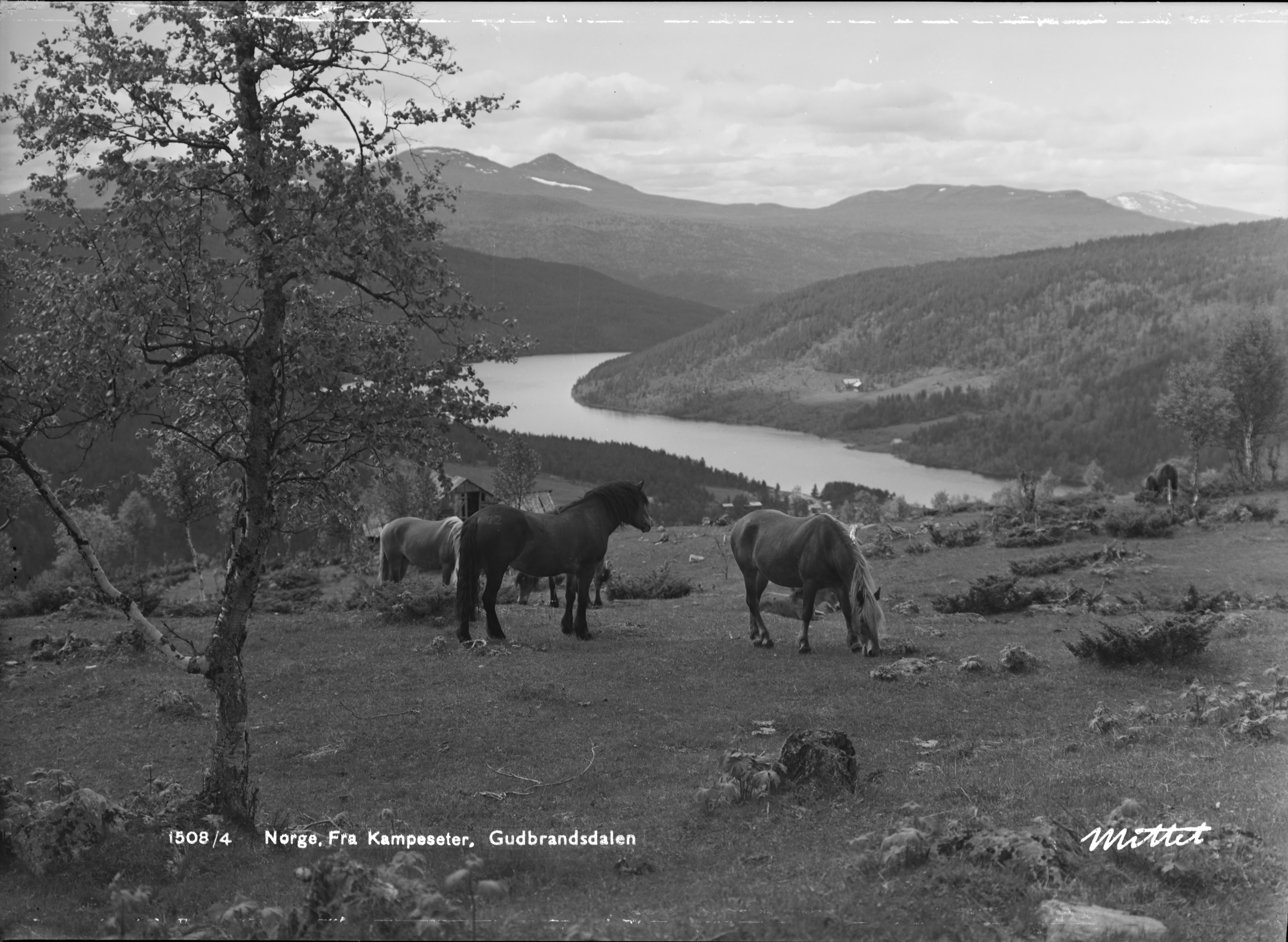

Food Traditions from Lillehammer and Gudbrandsdalen

Porridge | Meat | Vension | Fish

Flatbread, griddle cake and bread

Local traditional soup dishes

‘Kål’ (cabbage) was once the best dinner you could wish for in Gudbrandsdalen; a soup made with pearl barley, bacon, and other meats – and later also with potatoes and peas. It was hardly ever made with cabbage. After the autumn slaughter, a soup called ‘sodd’ – in which pearl barley was replaced with fresh meat and potatoes – was a popular dish. These dishes are today considered everyday cuisine, but once they were reserved for special occasions only.

In winter, a dish known as ‘mysusuppe’ – a soup prepared with acid whey and barley meal – was common in the northern part of Gudbrandsdalen. Further south in the valley, people often made cheese from the acid whey and then used this as basis for the soup. The soup was served with butter, cheese, and flatbread.

Porridge was a staple food in the old farming community in Gudbrandsdalen. As the most readily available cereal grain was barley, the porridge was often made from barley meal. The everyday version was caller ‘vassgraut’, and was a gruel based on barley meal and water.

Porridge was also used for special occasions, and ‘rømmegrøt’ (made from sour-cream) or ‘melkegrøt’ (made from milk) was often served at gatherings, weddings, and wakes. When rice arrived in the late the 1800s, ‘risengrynsgrøt’ – a rice-based porridge – became a popular dish served on festive occasions.

Porridge is still widely used today – either alone as an everyday dish or served with cured meats and flatbread in more formal settings.

At Heidal Ysteri, ‘rømmegrøt’ is made using the traditional recipe from the mountain dairy farms in the early 1900s.

Meat

Local suppliers:

- Brimi Sæter – cured ham and sausages

- Høyfjellsmat fra Skåbu

- Aukrust gard og urteri – cured sausages

- Dovrelam – cuts of lamb, salted & dried ribs of mutton, cured leg of mutton

- Annis Pølsemakeri – producer of Gudbrandsdalen’s most renowned sausages!

- Hafjell Slakteri

- Mogard gårdsmat – meatballs, fricadellen, pork variety meats, and cured sausages

- Bjorli fjellmat – venison (elk and reindeer), cured leg of mutton, salted & dried ribs of mutton, lamb charcuteries, cured sausages, variety meats, etc.

- Breheimen Mat – cured ham and sausages

Meat was usually preserved using techniques such as drying, salting, smoking, curing, fermentation, or a combination of these.

The most common cooking method was to boil the meat together with various vegetables and grains. When the meat grinder arrived in Gudbrandsdalen in the 1900s, it brought great advances in meat processing. Meatballs, fricadellen, meat patties, and sausages became everyday fare.

Cured sausages are often made from cuttings and the less desirable parts of an animal. Livestock as well as game can be used, and various seasoning is usually added.

Vension

Cured venison sausages and elk fricadellen/burgers are produced by:

- Høyfjellsmat fra Skåbu

- Bjorli Fjellmat

- Breheimen mat

- Mogard gardsmat

Gudbrandsdalen has a long tradition of big-game hunting – particularly for wild reindeer and elk. Big game was vital as it provided a plenty of food and a range of nutrients, and was also useful for other items necessary for survival.

Petroglyphs depicting elk (at Fåberg and Vinstra) and pitfall traps for both elk and reindeer in Gudbrandsdalen show the importance of hunting and gathering throughout history.

Venison was usually preserved as other meats, using salting and drying. It was also used as an ingredient in offal mixes and sausages.

Fishing in lakes and rivers has been important throughout history. In settlements by rivers and lakes, it is evident that fish – which was relatively fatty – was a vital food resource. Trout seems to have been the most popular, but perch, pike, and powan were also commonly used.

The traditional ‘lågåsildfisket’ (vendace fishing) at Fåberg by the lower part of river Lågen has been vital for the local economy, and is still a popular activity in early October when the fish head up the river to spawn.

‘Lutefisk’ is traditional dried whitefish soaked in lye. The lye, made from birch tree ashes or caustic soda, starts a breakdown process that leaves the fish easier to digest but with its nutritional value preserved.

Rakfisk (fermented trout) is a food tradition dating back to medieval times, and has long been a popular dish in Gudbrandsdalen.

Flatbread, lefse (griddle cake), and kaku (bread)

Producers of bakery products in Gudbrandsdalen:

- Ottadalen mølle: barley meal and pearl barley

In earlier times, the only bread used in Gudbrandsdalen was flatbread. It was, and still is, used with every meal. Flatbread was originally made from barley meal and water. The flour was always wholemeal and often made from low-quality grain. When cultivation of peas became common, peasemeal was used instead. Then the potatoes arrived, and with this a better quality flatbread. It was crispier and richer in flavour.

100-150 years ago, the word ‘lefse’ was used to describe a flat griddle cake that could be hard as well as soft. To make the soft version, people used rye flour, or a mix of barley meal and rye flour, and milk. When the potato was introduced, these soft griddle cakes became the most common – particularly in autumn and winter.

With the arrival of the oven and imported grains came the modern-day bread. Yeast-based bread baked in an oven is known as ‘kaku’ across large parts of Gudbrandsdalen. Porridge and flatbread could be made using local barley meal, but bread made with yeast required rye or wheat flour. People made their own yeast. When brewing beer, the froth was skimmed off, drained into a wooden barrel, and left to dry.

Sourdough was also used in the bread-making process. Some of the dough was stored dry until it was needed. When it was time to use it, some water or cultured milk was added and it was placed by the oven.

Fruit, berries, and herbs

Local suppliers:

- Moe gård: raspberries and raspberry juice

- Den lille tytingfabrikken: blueberry, lingonberry, cloudberry, and rhubarb jam

- Aukrust gard og urteri: large selection of herbs

- Per Otto Kaurstad: strawberries and strawberry juice

- Heggerud Gard: raspberries and vegetables

Berries from the garden and the wild were not commonly used until 1900. Then sugar became more affordable, and autumn had suddenly turned into a busy juice-and-jam-making period.

Cloudberries were more sought-after than other berries – first as a remedy against scurvy (in the 1700s) and later as dessert.

Lingonberries were used to make ‘troll cream’ (whole lingonberries with whipped egg whites and sugar), but blueberries only became popular when sugar was no scarce. The focus on health and antioxidants over the past decades has sparked a renewed interest in berries.

Beer brewing traditions

As in other parts of the country, beer brewing in Gudbrandsdalen is an old tradition. Beer was popular as a thirst quencher, as an alcoholic beverage, and as a nutrient. Home-brewed malt beer was essential during festive periods as well as at wakes. All farm work during the warm season required beer, and as the work – sowing, haying, and harvesting – almost overlapped, beer was readily available most of the summer.

Beer was brewed using malted barley. Every farm had a “malt storage bin”, and being a skilled brewer was important. Dried malt could be stored for years if it was kept dry.

The distillery Lillehammer Brænderi was established in 1847, and in 1852 the operation was expanded to beer brewing. Drinking habits had changed in the 1840s, and people consumed more beer and less liquor. The brewery at Lillehammer closed down in 1983, but reopened as the microbrewery Lillehammer Mikrobryggeri in 2006. Today, the brewery produces beer for use at the premises.

Ruten mountain brewery in Espedalen opened in 2008, and produces a selection of beer served at Ruten Fjellstue. Hubertus brewery is a small artisan brewery producing Belgian-style beer using Norwegian mountain spring water from own well.

PHoto: Cathrine Dokken

One of the oldest varieties is the ‘pultost’ – a strong, mature sour-milk cheese. Together with products such as butter and ‘gubbost’ (sweet brown cheese), ‘pultost’ dates back to the early mountain dairy farming in Gudbrandsdalen.

Today, old cheese-making traditions live on through several local cheese producers in Gudbrandsdalen. Two of these, Avdem and Brimi Sæter, are the proud winners of several Cheese World Championships awards. Avdem Gardsysteri produces traditional Norwegian cheese and dairy products, such as ‘pultost’, ‘prim’, ‘gubb’, ‘kvitkjuke’, and butter. Also on offer are the brown cheese ‘Huldreost’ and the French-inspired, unpasteurised, red-rind cheese ‘Fjelldronning’. Brimi Sæter focuses on sour cream, butter, ‘pultost’, and ‘kvitost’ – a semi-soft white cheese. The mountain-farm milk is a better ingredient than ordinary cow’s milk. High-mountain pastures add their own special quality to the milk and, in turn, more flavour to the cheese.

Heidal Ysteri uses traditional 1920s methods to produce its Heidalsprim (whey cheese) and Heidalsost (brown cheese) – both of which have a sweet and rich flavour.

Avdem, Brimi Sæter, and Heidal Ysteri are keeping alive old cheese-making traditions that may otherwise have been lost forever!

Gudbrandsdalsost

Gudbrandsdalsost is the most famous of the brown cheeses, and is a common feature on all Norwegian breakfast tables. This traditional product is a favourite sandwich topping and the pride of the nation. It is also almost unique to Norway. ‘Brunost’ (brown cheese) is a term used for brown cheese made from whey and added cow’s or goat’s milk.

Gudbrandsdalsost originates from Solbråsetra at Gålå. In the summer of 1863, a young dairymaid, Anne Hov, did something that was considered a total waste – she added cream to the whey! With this, Gudbrandsdalsost was born. At Solbråsetra the mountain-farm traditions are still upheld, and in summer you can still meet the dairy maid and taste freshly-made Gudbrandsdalsost.

Did you know that the village of Ringebu is home to the world’s largest cheese slicer, and that the cheese slicer was invented by Thor Bjørklund from Lillehammer in 1925? The original Bjørklund cheese slicer is still in production.